Brasil! Brasil! The Birth of Modernism - part 1

at the Royal Academy of Art.A wonderful exhibition exploring Brazilian art history through the work of ten artists, active between 1910 and the 1970s. During that time a flourishing in the arts - including painting, sculpture, graphic design, architecture, music and literature - swept across the country, and was known collectively as Brazilian Modernism. This was not a defined movement but rather a coming together of different cultural figures who campaigned for Brazil to move away from the old-fashioned traditional forms of art that were rooted in the colonial (1500-1815) and Imperial (1815-89) periods before Brazil became a republic in 1889. As a young, ambitious and optimistic nation, Brazil wanted to create its own distinctive identity. It rejected European tastes for academic art and typical subjects such as historical allegories and religious scenes in favour of those that reflected and celebrated the country's cultural diversity.Brazil has a significant Indigenous population but one that has been increasingly marginalised following the influx of immigrant settlers that began during the colonial period. Portuguese colonists forcibly brought more than four million enslaved people from West Africa across the Atlantic, with the aboliton of slavery only taking place in 1888. Later, significant populations of Italians, Japanese, Germans and Syrians settled in Brazil, further enriching its extraordinary ethnic diversity.

Although many modernists lived and studied abroad, mainly in Europe or the US, they returned to Brazil determined to fashion a new artistic identity that looked inwards rather than outwards for inspiration. Aside from incorporating modern approaches to art, artists travelled acrross the country reflecting on the different peoples and places they encountered and integrating them into their work. This exhibition celebrates this 60 year period, revealing the gradual move from the representational to the abstract.

Roberto Burle Marx (1909-1994):

Marx's affinity for native Brazilian plants saw him become one of the most influential landscape architects of the 20th century.

He studied visual arts but was interested in garden design and contributed to the landscape design of the new capital city Brasilia, inaugurated in 1960. From 1934 to 1937, he was the director of parks and gardens in Recife, the capital of the state of Pernambuco. Upon returning to Rio, he designed numerous gardens for private clients as well as large-scale municipal projects such as the famous mosaic pavements of Copacabana and Flamengo. He became celebrated for his landscape garden designs and planting schemes but continued to paint throughout his life.

Farm with Seven Piglets, 1943, (oil on canvas)

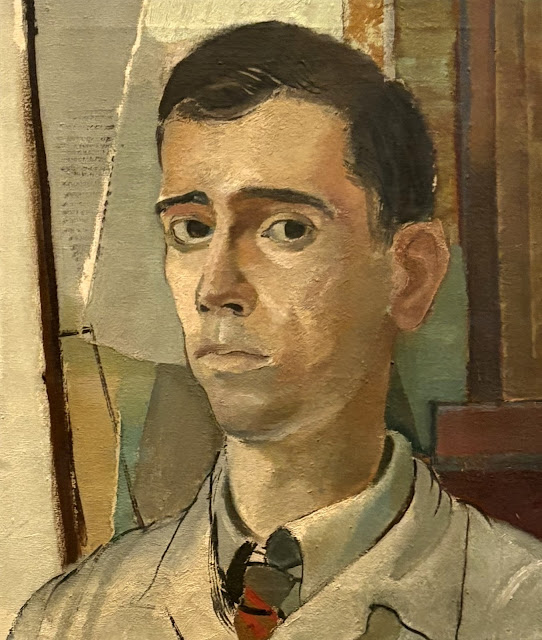

Portrait of a Young Man, 1943, (oil on canvas)

Landscape, 1943, (oil on canvas)

Anita Malfatti ( 1889-1964):

Malfatti was a trailblazing artist whose modernist paintings shocked the Brazilian establishment. She was born in Sao Paulo but her family moved to Berlin when she was 10. She returned to Brazil in 1916, where she held the Exposicao de Pinctura Moderna Anita Malfatti, in Sao Paulo, clearly positioning herself as a modernist artist. Her work depicted ordinary Brazilians going about everyday tasks, hitherto a subject deemed unworthy for paintings. The show was the first to challenge the orthodoxy of academic-based art, and as such is celebrated as the first modernist exhibition in Brazil. However, it was harshly criticised at the time; the impact on Malfatti was long-lasting and caused her to be a less progressive artist going forward. Nonetheless, having befriended many in Sao Paulo's modernist circles, she was to be a pivotal figure in the Modern Art Week that took place in the city in 1922. This event played a crucial role in briging Brazilian Modernism to prominence.

In 1923 Malfatti moved to Paris and exhibited at the Salon D'Automne in 1927. She returned to Sao Paulo in 1928 but the days of her experimental and progressive art were behind her.

First Cubist Nude, 1916, (oil on canvas)Russian Student, 1915, (oil on canvas)

Portrait of Mario de Andrade, 1923, (oil on canvas)

Yellow Man, 1915/16, (oil on canvas)

Japanese Man, 1915/16, (oil on canvas)

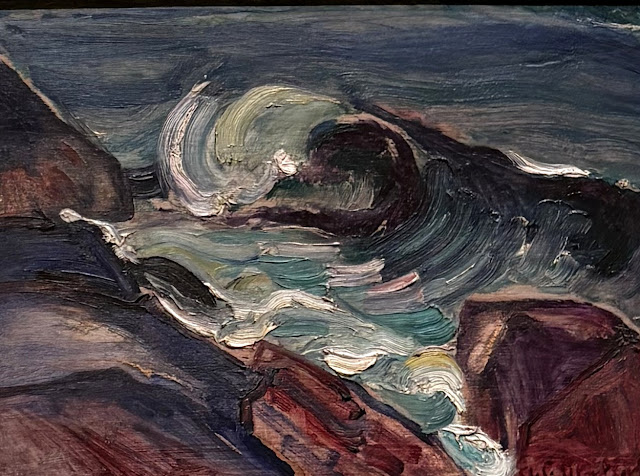

Seascape, Monhegan, 1915, (oil on canvas)

Wave, 1915-17, (oil on wood)Seascape (Cliffs), 1915-16, (oil on wood)

Lighthouse, 1915, (oil on canvas)

Portrait of Oswald, 1925, (oil on canvas)

Chinese Woman, 1921-22, (oil on canvas)Man of Seven Colours, 1915/16, (pastel and charcoal on paper)

Lasar Segall, 1889-1957:

As an outsider in both Brazil and Europe, Segall explored themes of social injustice, oppression and immigration in his paintings. Born in Vilnius, Lithuania, to a Jewish family, he studied in Germany. He first visited Brazil in 1913, spending the year meeting fellow artists and intellectuals and exhibiting and selling his work. Upon returning to Europe, he became one of the leading figures of the Dresden Expressionist movement.

In 1923 Segall migrated to Sao Paulo. Alongside Anita Malfatti and Tarsila do Amaral, he founded the Sociedade Pro-Arte Moderna which aimed to promote modern art; he acted as its director until 1935. Despite being embraced by Brazil's modernists, such acceptance was not universal, and his work was at times subject to anti-immigrant and anti-Semitic attacks.

Lucy with Flower, 1939-42, (oil on canvas)

Mixed-Race Woman with Child, 1924, (oil on canvas)Brazilian Landscape, 1925, (oil on canvas)

Mixed-Race Boy II, 1924, (oil on canvas)Banana Grove, 1927, (oil on canvas)

This composition speaks to the influx of European migrants who arrived to work on Brazil's agricultural plantations following the abolition of slavery in 1888.

Pogrom, 1937, (oil and samd on canvas)

Towards the end of the 30s and 40s Segall turned away from the colourful landscapes of Brazil and created works that demonstrated his concern with the suffering that was occurring in Central and Eastern Europe at the outset of WWII. In Pogrom (devastation in Yiddish), a pile of corpses fills the painting, depicting one of many anti-Semitic massacres perpetuated during the period. It is a scene of destruction and horror, yet overhead a dove can be seen flying, perhaps used by Segall as a symbol for peace.

Light Reflecting in the Forrest, 1943, (oil on canvas)

Favela, 1954-55, (oil and sand on canvas)

Between 1890 and 1930, favelas emerged on the hillsides of Rio de Janeiro in the wake of the city's demolition of corticos (high-density tenement blocks) to combat a public health crisis, which forced those of the poorer polulation into the streets. Initially consisting of wooden shacks and with no access to public services, favelas were perceived as places of extreme poverty and crime. Over time, however, they were viewed more sympathetically.

Portrait of Mario de Andrade, 1927, (oil on canvas)

Boy with Geckos, 1924, (oil on canvas)